Stefon Harris & Blackout – What A Wonderful World (Live from PASIC 2024)

Stefon Harris & Blackout – I Know Love (Live from PASIC 2024)

Stefon Harris & Blackout – Chasin’ Kendall (Live from PASIC 2024)

Stefon Harris & Blackout – Blackout (Live from PASIC 2024)

University of South Carolina – Jolene (Live from PASIC 2024)

University of South Carolina – to the boy from venus, with love (Live from PASIC 2024)

University of South Carolina – Insomnia (Live from PASIC 2024)

pax duo – Bloom Suite

pax duo – Emigre and Exile

pax duo – untitled (Live from PASIC 2024)

Tomasz Arnold – Houdini’s Last Trick

Harnsberger/Jones Duo – In The Midst of Darkness (Live from Lee University)

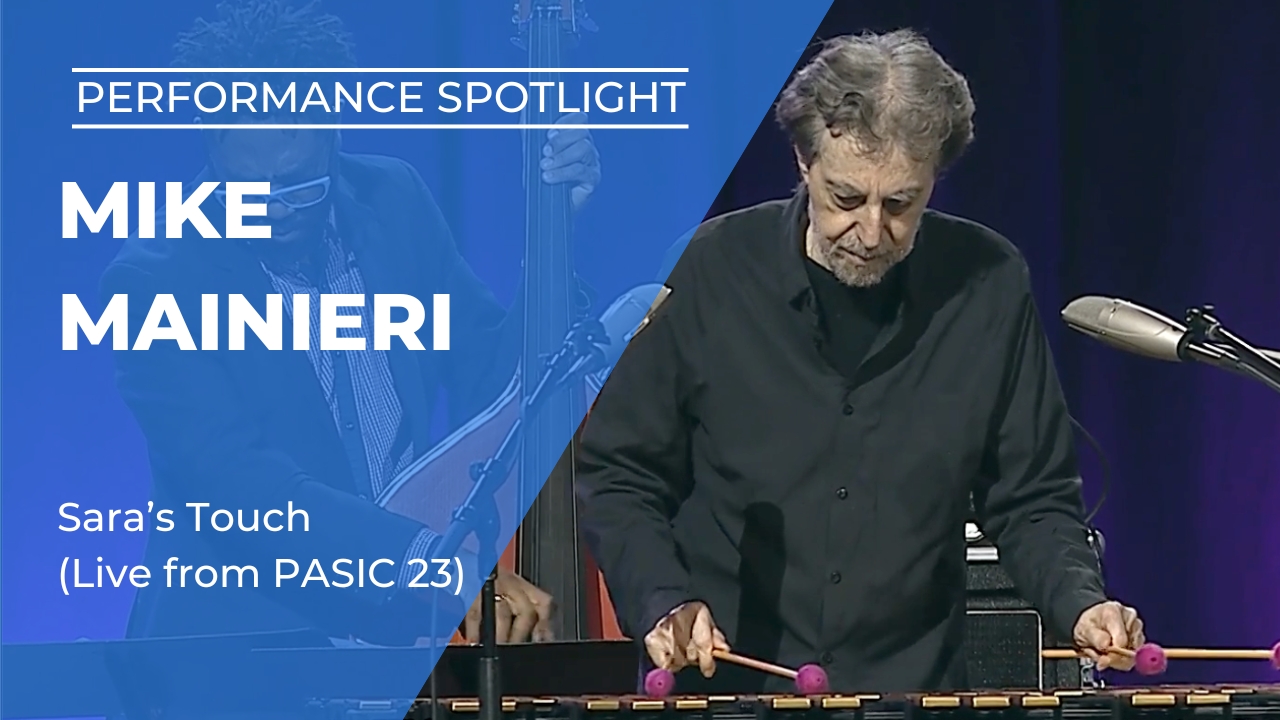

Mike Mainieri with Andy Narell/Luis Perdomo Group – Sara’s Touch (Live at PASIC 23)

Mike Mainieri with Andy Narell/Luis Perdomo Group – Bullet Train (Live at PASIC 23)

Oliver Mayman – Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right (Live from Steve Weiss Mallet Festival)

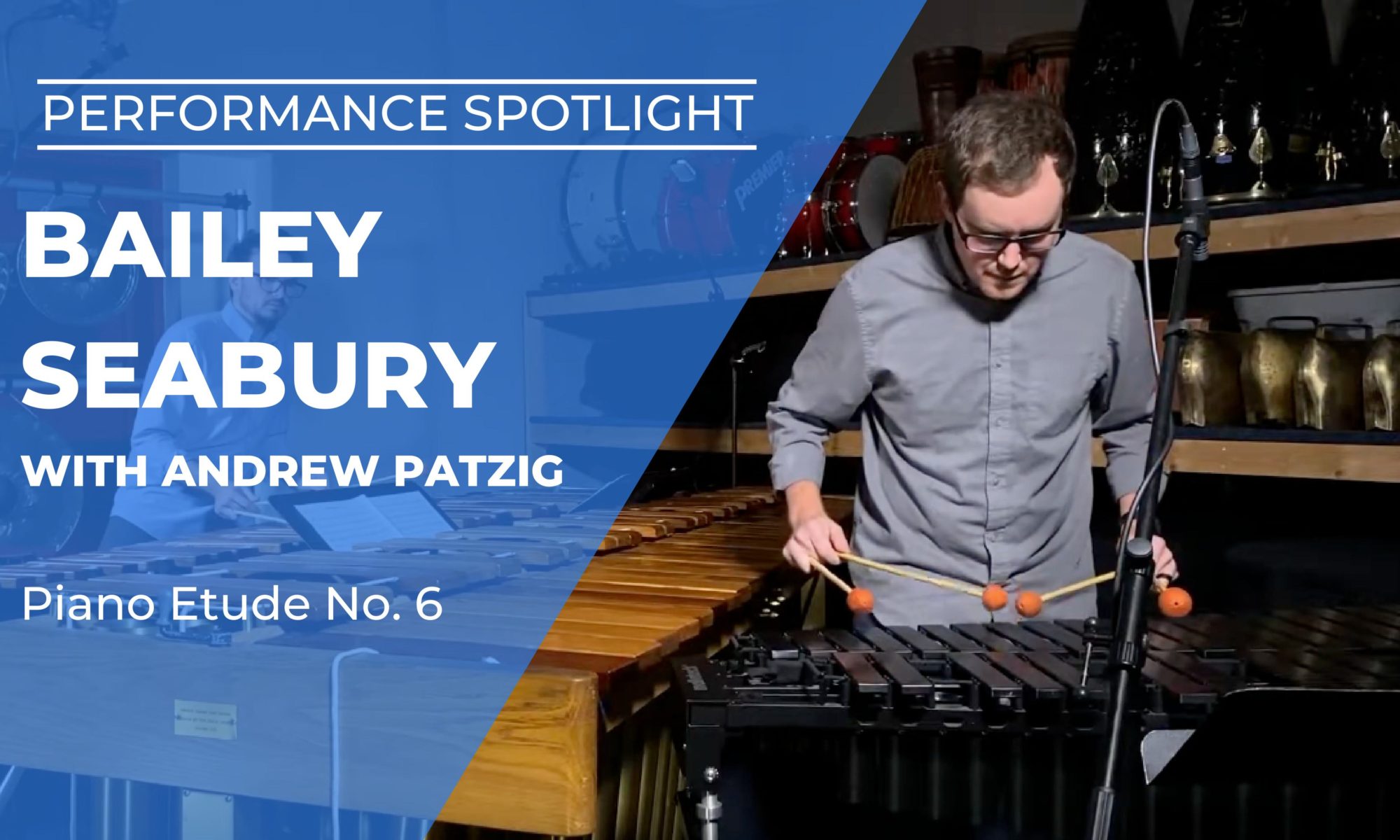

Bailey Seabury with Andrew Patzig – Piano Etude No. 6

Iwaki Senda – The Source

Hyeji Bak – Attraction

Mark Boseman – Velocities

Marta Klimasara – Reflections On The Nature Of Water (excerpt)

Joe Locke – Landslide

Tony Miceli – Hot House (Live at Chris’ Jazz Cafe)

Eastman Percussion Ensemble – Passage to an Uncharted World (Live at PASIC ’22)

Eastman Percussion Ensemble – The Inexorable Motion of Time (Live at PASIC ’22)

OmegaAir with Stefon Harris: More Liberating Expression

Stefon Harris demonstrates and talks about how the natural half-pedal sound of the Malletech OmegaAir grants him more liberating expression when he plays.

OmegaAir with Stefon Harris: Vertical Dampening

OmegaAir with Stefon Harris: The Half-Pedal Sound Without The Pedal

Stefon Harris demonstrates how the Malletech OmegaAir can produce a half-pedal sound, without actually having to step on the pedal.

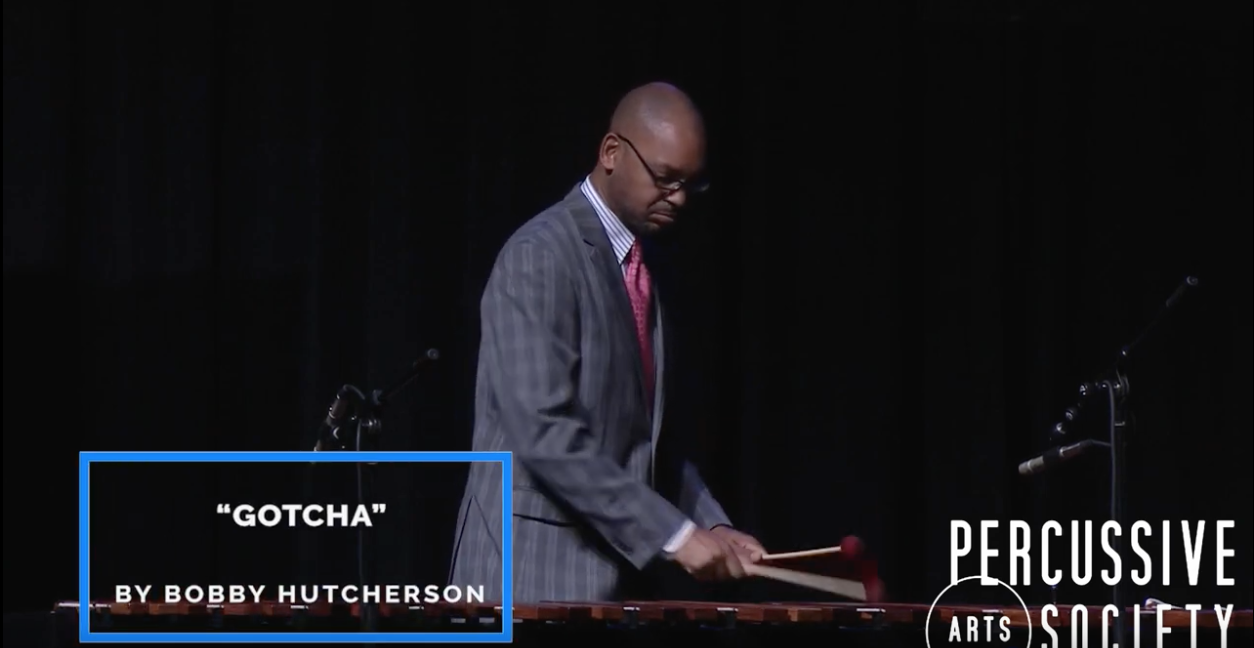

PASIC ‘100 Years of Vibraphone’ Celebration Concert – “Gotcha” by Bobby Hutcherson

This performance was shot November 10th, 2021 as part of the Percussion Arts Society’s “100 Years of the Vibraphone” Celebration Concert in Indianapolis, Indiana. All videos feature Malletech products including the OmegaVibe, Stiletto Rosewood Marimba, the MJB “Black” Marimba, and various Malletech mallets.

Jason Marsalis – Marimba

Stefon Harris – Vibes/Marimba

Joe Locke – Vibes

Keith Brown – Piano

Ben Williams – Bass

Obed Calvaire – Drums

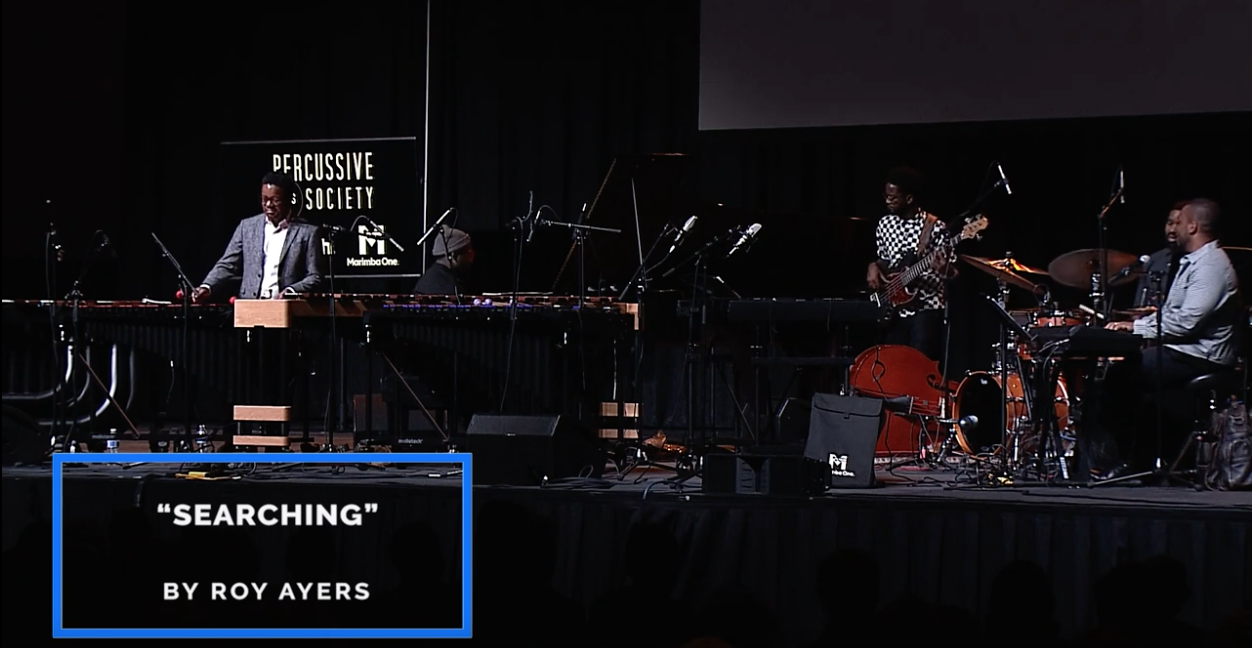

PASIC ‘100 Years of Vibraphone’ Celebration Concert – “Searching” by Roy Ayers

This performance was shot November 10th, 2021 as part of the Percussion Arts Society’s “100 Years of the Vibraphone” Celebration Concert in Indianapolis, Indiana. All videos feature Malletech products including the OmegaVibe, Stiletto Rosewood Marimba, the MJB “Black” Marimba, and various Malletech mallets.

Warren Wolf – Vocals

Stefon Harris – Vibes

Keith Brown – Piano

Ben Williams – Bass

Obed Calvaire – Drums

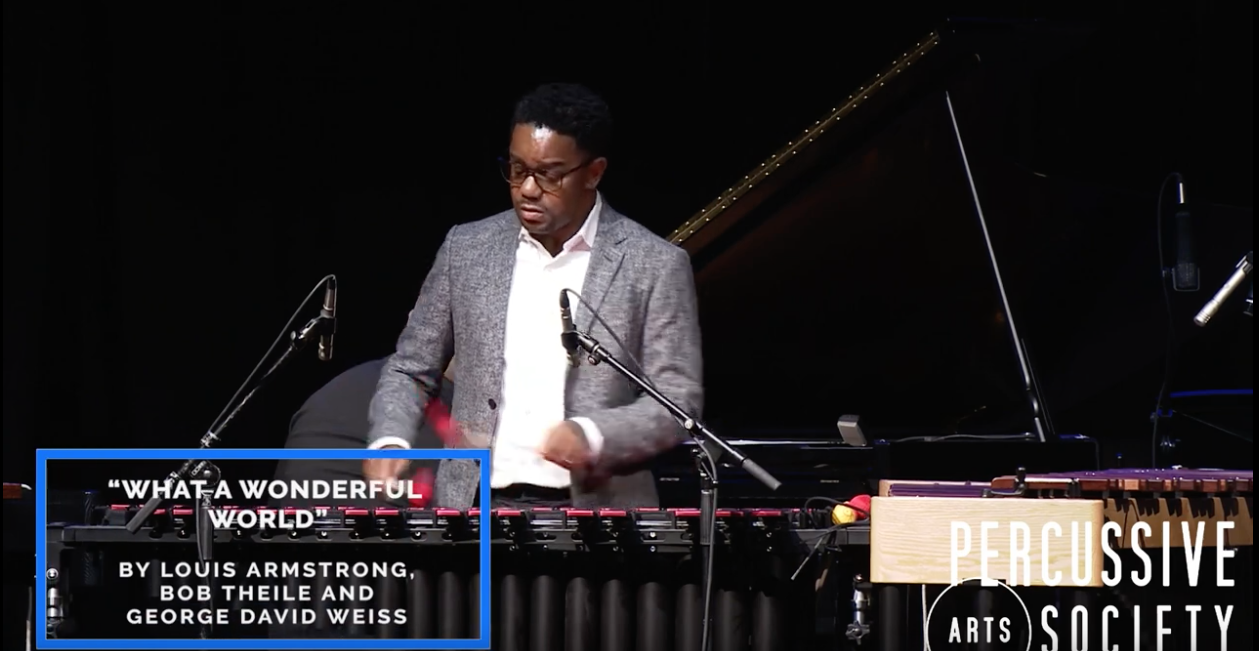

PASIC ‘100 Years of Vibraphone’ Celebration Concert – “What A Wonderful World” by Louis Armstrong

This performance was shot November 10th, 2021 as part of the Percussion Arts Society’s “100 Years of the Vibraphone” Celebration Concert in Indianapolis, Indiana. All videos feature Malletech products including the OmegaVibe, Stiletto Rosewood Marimba, the MJB “Black” Marimba, and various Malletech mallets.

Warren Wolf – Vocals/Keys

Stefon Harris – Vibes

Keith Brown – Piano

Ben Williams – Bass

Obed Calvaire – Drums

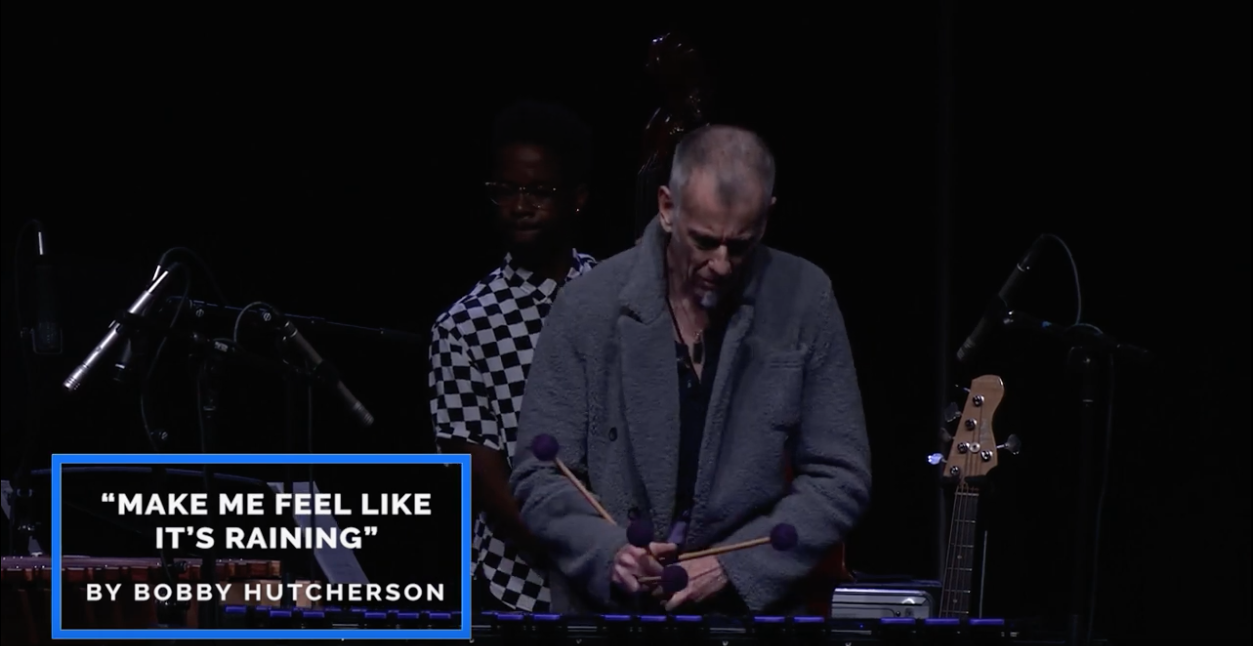

PASIC ‘100 Years of Vibraphone’ Celebration – “Make Me Feel Like It’s Raining” by Bobby Hutcherson

This performance was shot November 10th, 2021 as part of the Percussion Arts Society’s “100 Years of the Vibraphone” Celebration Concert in Indianapolis, Indiana. All videos feature Malletech products including the OmegaVibe, Stiletto Rosewood Marimba, the MJB “Black” Marimba, and various Malletech mallets.

Joe Locke – Vibes

Keith Brown – Piano

Ben Williams – Bass

Obed Calvaire – Drums

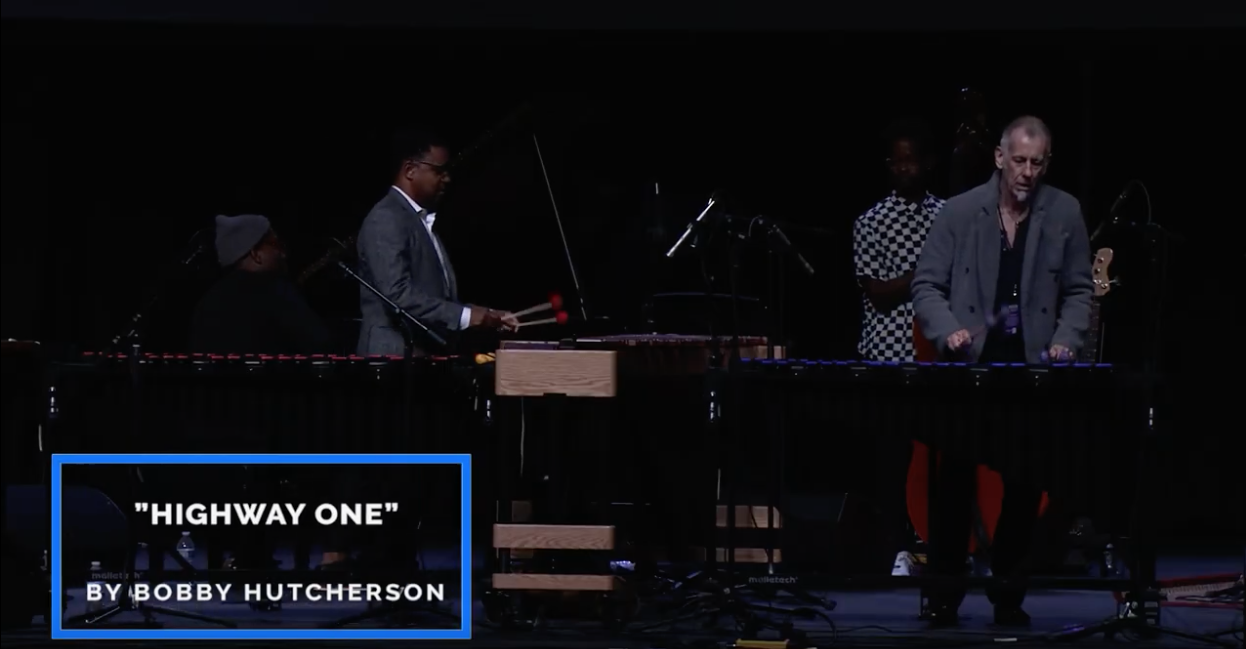

PASIC ‘100 Years of Vibraphone’ Celebration Concert – “Highway One” by Bobby Hutcherson

This performance was shot November 10th, 2021 as part of the Percussive Arts Society’s “100 Years of the Vibraphone” Celebration Concert in Indianapolis, Indiana. All videos feature Malletech products including the OmegaVibe, Stiletto Rosewood Marimba, the MJB “Black” Marimba, and various Malletech mallets.

Joe Locke – Vibes

Stefon Harris – Marimba/Vibes

Keith Brown – Piano

Ben Williams – Bass

Obed Calvaire – Drums

LHS Talks about the OmegaVibe

Drum and percussion video projeckt by percussionist Tuomo Huhdanpää goes to Frankfurt Musik Messe 2017. Tuomo is checking the Malletech Omega Vibe with Leigh Stevens, founder of Malletech company. Full interview.

Andy Harnsberger – Saragorda Sound

Frozen Earth Duo – Des pas sur la neige

Vibraphone Discussion with LHS and Tony Miceli

This discussion with Leigh Howard Stevens and Tony Miceli was hosted on Facebook Live by Steve Weiss Music.

Andy Harnsberger – “Tala” from Traveller

Frozen Earth Duo – the lonelyness of Santa Claus

Scott Herring – From Our Homes To Yours

Scott Herring performs the following repertoire as part of the South Carolina Philharmonic’s “From Our Homes To Yours” video series.

- “Dr. Gradus ad Parnassum” from Children’s Corner by C. Debussy

- “Andante” from Sonata in A minor by J.S. Bach

- Virginia Tate by P. Smadbeck

Andy Harnsberger – Practice Strategies

Andrea Venet – Green Ranger

Tony Miceli – I’ve Grown Accustomed To Your Face

Andy Harnsberger: Establishing a Daily Routine

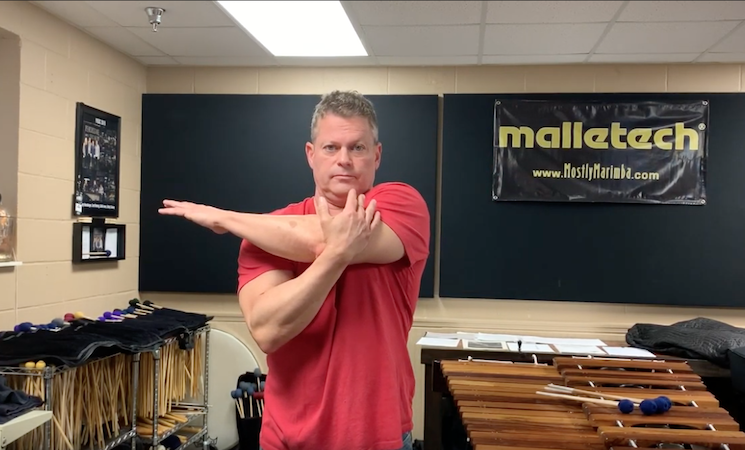

Andy Harnsberger: Stretching for Pain-Free Practice

Michael Burritt – The Fragile Corridor

Available for purchase here

Andy Harnsberger – “Guangzhou” from Traveller

Escape X – Clear Midnight

Andy Harnsberger – UTA IV

Brant Blackard – Rounders

Cameron Leach – Spiel

Andy Harnsberger – Dead Reckoning

David Friedman & Tony Miceli – PASIC 2018

used with permission from the Percussive Arts Society

Andy Harnsberger – Unbreakable

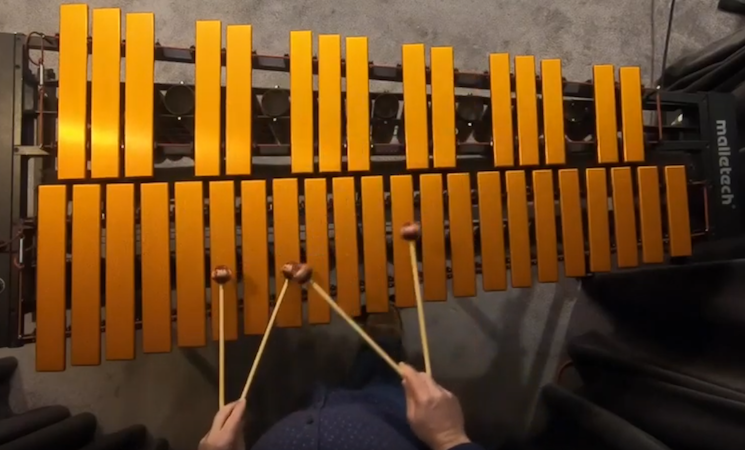

MTech 4.3 Product Demo video

Escape X – My Favorite Things

The Guide To Practicing Late In An Apartment

The Guide to practicing the Marimba or Vibes Late In An Apartment or With A Baby (even late at night).

by Tony Miceli

I think I have this totally figured out. Vibraphonist Carolyn Stallard came over and we experimented with the Late Nite Mallets (click here for the mallets).

We played on my first floor and went and took turns listening in the basement. If this was an apartment it would be a poorly designed apartment. I imagine most apartments have better insulation than the floor to my basement.

First the Late Nite Mallets really cut the sound down. You can really hit the instrument and work on your hands without producing a lot of sound and bothering someone. No more playing with soft mallets but still playing very very softly. The Late Nite Mallets will produce just enough sound for you to hear the instrument and the articulation. It’s totally acceptable. No one in the next room would hear the music, or at least hear a tiny tiny bit of it. So problem solved, you have a baby sleeping in the next room but you want to practice or you have your baby in a snugly and you want to practice and keep the baby asleep; You can do it.

The next problem was getting rid of the thud we were hearing in the basement. Well actually it was reducing it as much as we could. We really reduced it a lot. I put down two moving blankets and it made a difference, however I said to Carolyn we need more blankets. Carolyn being smarter than me said, ‘No we don’t, just fold these over. We just need them under the wheels’. So we did that and it looked like this.

Now we had the equivalent to 4 or 5 blankets underneath. The thud was reduced by about 85-90%. It was so quiet that I think most neighbors would be fine with it. With music or a tv on I think they wouldn’t notice it.

We talked about a neighbor who still complained and we thought of positioning the vibes over a room that wasn’t used a lot. Maybe positioning the vibes over the neighbor below’s kitchen? Maybe their bathroom? Maybe their bedroom during the day? You may need to experiment here and maybe even get the neighbor involved.

We were both amazed at how the Late Nite Mallets and the moving blankets made a difference. You couldn’t play with regular mallets in most apartments, especially late at night. The mallets reduce the sound of the instrument so much that neighbors won’t hear the vibes. And the rug takes care of the thud! That means you can practice now all night! No excuses!!!!

used by permission from vibesworkshop.com

Late Nite mallets – Leigh Howard Stevens demo

Late Nite mallets – Tony Miceli demo

Check out this demonstration video of our new Late Nite series of low-volume practice mallets, now available through your favorite percussion retailer.

Conversations with Stefon Harris

NYU Steinhardt Jazz Interview Series at SubCulture in New York. Dr. David Schroeder interviews virtuosic vibraphonist, passionate educator, forward-thinking entrepreneur, and NYU faculty member Stefon Harris.

What is a Xylorimba?

By Bob Becker, first published June 1, 2005

(Are the overtones tuned differently in various ranges of its keyboard?)

The term ‘xylorimba’ clearly refers to some kind of hybrid instrument, but it depends on who is using the term, and when. Even the word itself is a composite: xylo is the common Greek root meaning ‘wood’; and rimba is an arbitrary clipping of the word ‘marimba’, which itself comes from an African (Bantu) root meaning ‘tongues’. Xylorimba is indicated in music by various European composers (for example, Messiaen and Boulez), but in the scores there is no information given regarding overtone tuning. In a number of works (Couleurs de la cité céleste, for example), Olivier Messiaen calls for a xylophone, a marimbaanda xylorimba, suggesting that he had a very specific type of instrument in mind. In some scores (Des canyon aux étoiles, for example) Messiaen gives specific ranges, varying from 4 to 4.5 to 5 octaves, as well as the clarification that in his notation the xylorimbasounds as written. On the other hand, Pierre Boulez writes for the xylorimba in Le Marteau sansmaître as a transposing instrument (“f to f écrit” is shown as sounding one octave higher). In Pli selon pli Boulez even calls for two 5.0 octave xylorimbas, also written as sounding one octave higher than written. Both composers indicate C8 as the top note on a xylorimba (the same highest sounding note on a standard xylophone). The lowest pitch for the 5.0 octave xylorimba in these scores is C3, sounding one octave below middle C.

Both the Premier company in England, and Bergerault in France have marketed instruments called xylorimbas, described in catalogues as having a 5.0 octave range (C3 to C8); however, I have not tested the overtone tuning on either of these models myself. For a number of years Premier manufactured a 4.0 octave C4 to C8 ‘xylophone’, an instrument that was tuned throughout its range the same as their marimbas – with the second partial two octaves above the fundamental. I know because I played on this model during tours of the UK in the 1980s. Some of the old Deagan catalogues list, and picture, instruments called xylorimbas – the 730 series. Although the catalogues give no information about overtone tuning, the examples I have seen and tested were tuned like standard marimbas. The Deagan 730 xylorimbas had a relatively small 3.0 octave range: C4 to C7, or F4 to F7, and were marketed on low-standing frames, as if they were meant to be played from a seated position (possibly to be used by pit drummers in the multi-instrument ‘trap’ setups popular during the 1920s and 30s). The Leedy Company in the United States produced 5.0 octave instruments that were called xylorimbas. I have seen and played only one example of these, and the overtone tuning appeared to be usual marimba style (second partial two octaves above the fundamental) throughout the range. I personally have never encountered an instrument with two different overtone tunings on the same keyboard; although Claire Omar Musser is quoted in a 1932 magazine article as claiming that the instrument called a ‘marimba-xylophone’ is tuned with the second partial two octaves above the fundamental in the low range, and quint-tuned in the upper range. ‘Quint’ tuning is a method of placing the first overtone (i.e., the second partial) of a bar an octave and a fifth above the fundamental.

I have seen several Deagan instruments labelled with the word ‘marimba-xylophone’ – the 4700 series, for example – in fact I own one of them (a #4726). In my experience the overtones on these instruments invariably have been tuned exactly the same throughout the range. My instrument is 4.5 octaves: C3 to F7, and is tuned with the usual marimba overtones (second partial two octaves above the fundamental). According to the original Deagan catalogue the largest instrument in the marimba-xylophone series, model #4732, was six octaves: E2 – E8; however, it is unknown to me whether Deagan ever built one of them. I think the term marimba-xylophone refers to the upward extension of what is considered to be the highest octave of a standard marimba, although that’s all it is – terminology. Hal Trommer, who worked for Deagan for many years, has said the reverse: marimba-xylophones are really xylophones extended downward into the standard marimba range. For the earliest examples from before the 1920s, that would be equally true, because none of Deagan’s instruments from that time were overtone-tuned at all. They tuned only the fundamental and just left the overtones alone. It’s immediately audible on any old (pre-1920s) Deagan marimbas and xylophones that haven’t been retuned. For Deagan xylorimbas and marimba-xylophones produced before 1927, then, the question of multiple overtone tunings on the same keyboard is moot – no overtones were tuned.

Just as manufacturers, over the last several decades, decided to extend the standard marimba range downward, they also could extend the range upward without redefining what a marimba is. The same goes either way for xylophones – for example, the Deagan Artists’ Special xylophone #268 was five octaves in range: C3 to C8 (interestingly, the same sounding range as European xylorimbas). I also own a #268, but my instrument was retuned, using quint overtone tuning, at the Deagan factory sometime after 1940. Since I don’t know the year of manufacture for this particluar xylophone, I can’t be sure if the overtones were tuned originally and, if they were, in what way. The Deagan company introduced second partial tuning on their keyboard instruments in 1927, and J.C. Deagan himself declared that quint-tuning (his terminology) would be applied only to xylophones; however, there was no universal agreement about it being something that defined xylophone-ness. To this day, both overtone tuning and keyboard range are parameters determined entirely at the discretion of manufacturers, with a few companies offering various options to customers.

The only defining feature of the xylophone vis-á-vis the marimba, as far as composers and conductors are concerned, is transposition: the xylophone sounds one octave higher than written; the marimba sounds the written pitch. Performers have always been free to play either type of instrument with any kind of mallet they like – there’s no law against playing xylophones with yarn mallets or marimbas with rubber mallets. Even now it is common in Europe to find instruments marketed as ‘xylophones’ that are tuned like marimbas, have no resonators, and have keyboards configured like vibraphones. As long as it is made out of wood and is played as a transposing instrument, it counts as a xylophone. By this definition, Messiaen’s version of a xylorimba is really a marimba, because it’s made of wood and sounds as written; and Boulez’s version of a xylorimba is really a xylophone, as it’s defined as a transposing instrument. In fact, however, both composers are writing for thesameinstrument: Messiaen is consistent about showing the sounding pitch of the instrument (whether xylorimba, xylophone or marimba) by using numerous 8va and 16ma indications in his notation; Boulez writes for xylorimba (as well as xylophone) as a transposing instrument, defined in his scores as sounding one octave higher than written. Of course neither composer mentions overtone tuning one way or the other.

Bob Becker (June, 2005) Reprinted by permission

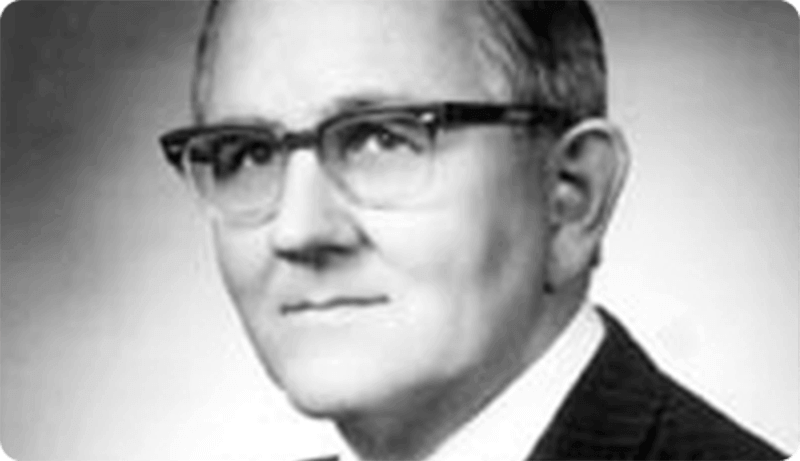

An Interview with Michael Burritt

How Leigh Stevens is Ruining My Life

I can’t believe how much I’m learning about the vibraphone. I spent the day with Leigh Stevens at the Malletech factory and once again learned so much about the instrument!

Leigh had me play the Omega for a bit. It sounded great. Then he told me to hang on for few minutes. He turned the heat up on the room. It went from 65 to 70. Then he had me play the Omega and it sounded SO … MUCH … BETTER.

But the experiment wasn’t over. He brought me out to the warehouse which was cool. Maybe 65 degrees? He had a Musser in the warehouse. He had me play it. It sounded terrible. We then brought the Musser into the warm room. I played it after a few minutes and it sounded so much better. The great thing about the Omega is you can tune the resonators. On my Musser I’m stuck with where they put it.

I learned so much about resonators in that experiment. It’s really amazing how much Leigh knows about all this.

Two nights ago I played a gig in a mansion. My instrument sounded terrible. I assumed it was me or my mallets. Didn’t know what I know now. The room was big and cold. The air in the resonators was too cold for the resonators.

I’m going back to Leigh’s and we are going to heat up the room to 85 and then tune the resonators and mark the settings on a stick: 85 degrees then 80, 75, 70 and 65. What you do is set the resonators up for the room and then, with a metal or wooden stick, put it in each resonator and make the depth. With the Omega you reach underneath and tune each resonator.

I’ll keep the marked measuring sticks with me for the important gigs! I was amazed to see the difference.

I can also say for sure now that I’m a felt guy. I’ve been playing on felt and gel now. I’ve been able to really compare the two. I am so used to felt and have so much more control over it. Maybe I can get used to gel but for now it’s felt. I think felt has more give. I feel like I can make it speak more!

And here’s how Leigh has ruined my life. The problem is I’m not an ignorant vibe player any more. That’s really screwing me up though. The more I learn about the instrument in a way, the harder it will get to play the instrument in other than perfect environments. Now I want to only play in 70 degree rooms. I’m going to buy a thermometer for my basement and will get one to bring to gigs. If it’s an important gig, I’ll probably tune the resonators to the temperature.

I think the more we all know about the instrument the pickier we will get and the more we will demand! That’s really exciting to me. Knowledge is power! This is a perfect example of how ignorance can really hide the truth.

As a result of my friendship with Leigh and hanging with him, my life as a performer on the instrument is ruined. I’m learning to hear the subtle changes of the instrument and how the environment changes all that. It’s bittersweet knowledge. I used to be ignorant to so many things about the instrument. Not any more. And of course I hope to ruin your lives as well! So I’ll pass on the knowledge!

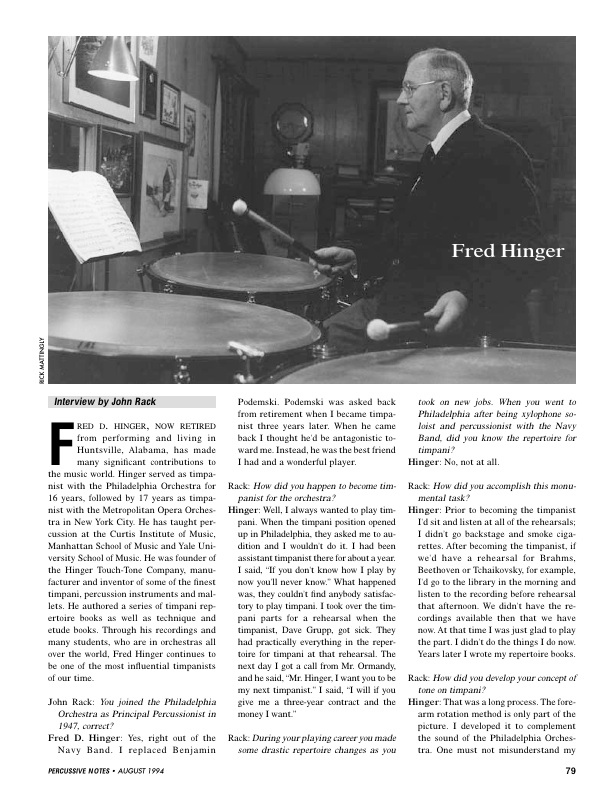

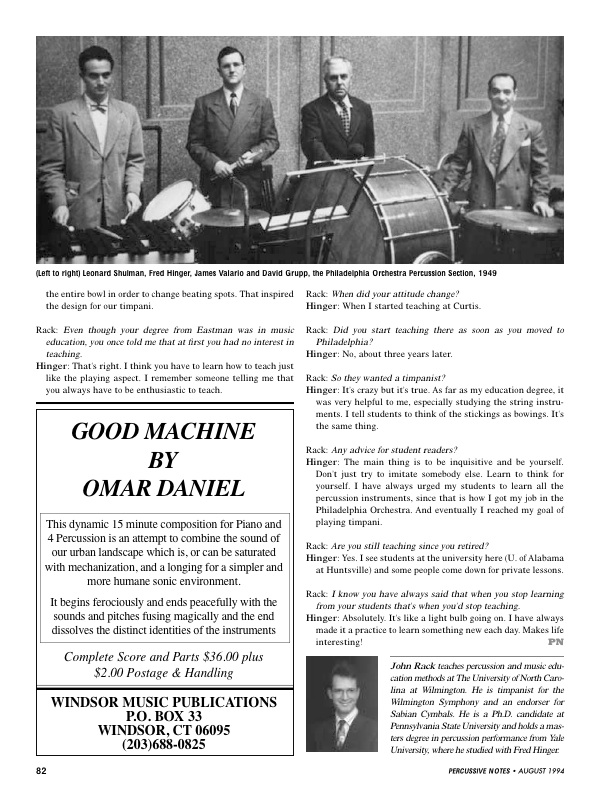

An Interview with Fred Hinger

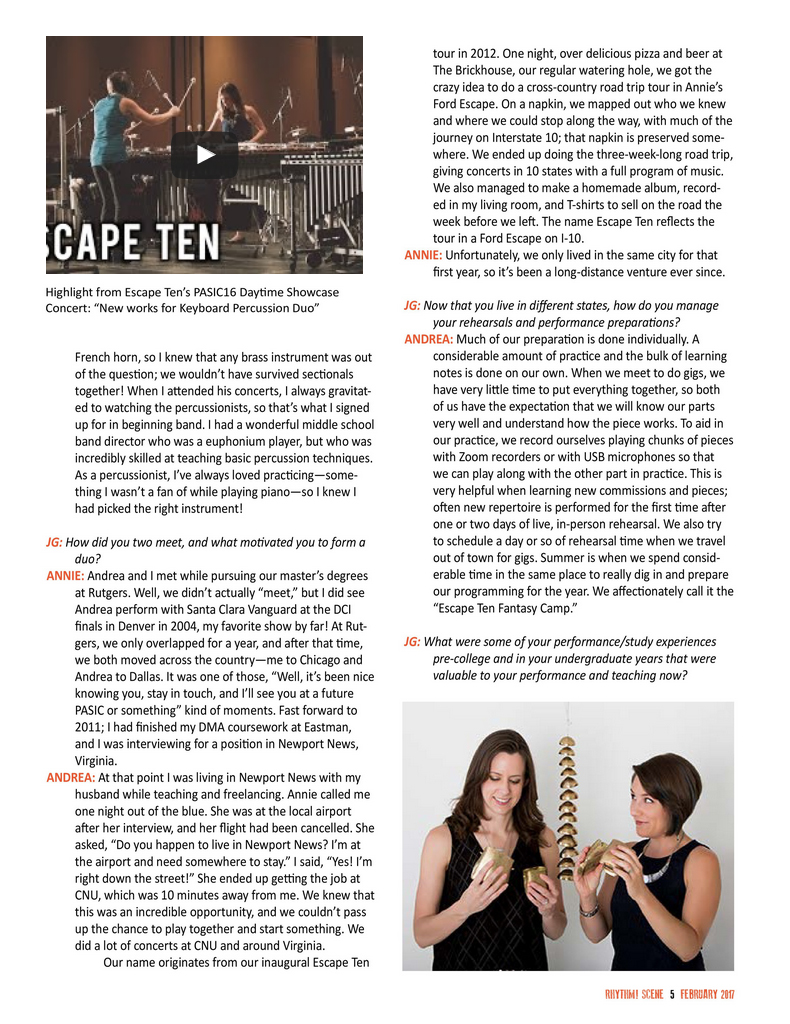

An Interview with Escape X

Xylophone vs. Marimba, More Thoughts

By Bob Becker, first published May 14, 2013

In April, 2013 I received an email from Jesse Strauss, a student at Belmont University, asking for my thoughts about an article by Vida Chenoweth in which she reached some conclusions about the terms ‘xylophone’ and ‘marimba’. I have discussed the distinctions that differentiate these terms in clinics, as well as in the Xylorimba article above. Below is Jesse’s email, and my response to him about it.

JS: I am a student at Belmont University, and I also attended the LHS seminar last summer – it was a pleasure seeing your clinic in both New Jersey and Nashville!

As I was flipping through an old anthology of percussion articles fromThe Instrumentalist magazine, I came across one by Vida Chenoweth entitled “The Differences Among Xylophone, Marimba, and Vibraphone” (published in 1961). I immediately thought back to your clinic and wondered how Chenoweth might approach the issue, so I read on. It was a brief article, but the conclusion she reached at the end was: “In short: (1) the xylophone is a percussion instrument with a wooden keyboard; (2) the marimba is a xylophone with resonators.” In other words, it seems as though she differentiates the instruments in the same way that we differentiate a rectangle and a square.

In comparison to what I drew from your clinic – that a xylophone is technically no different except that it sounds an octave higher than written – she even makes somewhat of a contradictory statement: “Some people mistakenly identify the xylophone as a treble marimba…”. So, I am wondering what your opinion is on the matter. Is the difference that you established in your clinic one that has evolved over the years, making this very old article simply out-of-date? Or was there really once disagreement or confusion over the topic, even among professionals such as Chenoweth and others? I am also curious about your own experience as you have traveled around giving this clinic; I imagine most students are stumped by the opening question, but do most professionals seem to know the answer? Or are even they scratching their heads on the topic?

BB: Vida Chenoweth is not only a great marimbist, but also a trained and experienced (ethno)musicologist and researcher. Her definitions of the terms xylophone and marimba are in line with many classic studies of organology, which is the study of musical instrument classification. If you read books like Curt Sachs’The History of Musical Instruments,you find the word xylophone as the principal heading for all wooden-keyed instruments. ‘Xylophone’ is a technical term, with classical Greek roots (xylo= wood; phone= sound), as I probably pointed out in my clinic. It’s similar to a term like metallophone; although xylophone is also a vernacular term that people use for many kinds of instruments, including toy glockenspiels. ‘Marimba’ derives from a Bantu root found throughout East Africa, which traveled with the Spanish slave trade to Central America, in particular Guatemala. In some organological texts the word marimba is used in a technical way to indicate the presence of resonators of any type, including the traditional African kinds made from spherical gourds. It would appear that is the view taken in Chenoweth’s article.

The first keyboard instruments made by the American percussion pioneer John Calhoun Deagan were, I believe, glockenspiels (real ones, with steel bars). The first documented xylophone he constructed was in 1893, and had only a diatonic keyboard and no resonators. The earliest marimbas manufactured in North America were produced by the J.C. Deagan company, and included a unique instrument called aNabimba– a word Deagan himself concocted, but obviously a take on ‘marimba’. The Deagan Nabimbas were available in ranges of 2.0, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, and 5.0 octaves (C2 to C7). Although modeled on Guatemalan marimbas, the resonators were tubular and made of brass, as opposed to the wooden box-style resonators found on Central American instruments. All of the Nabimba resonators, which were individually tunable, had the traditional African/Central American feature of a membrane mounted over a small hole (as on a kazoo), creating a buzzing effect for the sound. Clearly Nabimbas were a more modern copy of Guatemalanmarimba dobleinstruments heard in the US during tours by the famous Hurtado family around the turn of the century. J.C. Deagan studied the physics of musical acoustics, and his company became renowned for precise tuning as well as the inclusion of resonating tubes for each bar, whether on metallophones, xylophones, or marimbas. The resulting superior sound and projection of Deagan instruments made them the standard of excellence for several decades.

Despite Chenoweth’s academically accurate comments, I stand by my original statement that both the meaning and derivation of the terms ‘xylophone’ and ‘marimba’ depend onwhois using them (the terms as well as the instruments), andwhen. In my opinion, the modern North American xylophone is a hybrid instrument that evolved primarily through the efforts of manufacturers such as Deagan and later Leedy, as well as some player/designers who worked with them, like George Hamilton Green. Modern xylophones – at least the ones made by the major manufacturers in the US and Japan – share the same construction features with marimbas: rosewood keyboards, well-engineered frames, and precisely-tuned resonators. Some companies offer alternative overtone tuning (as introduced by Deagan in 1927); however, the main differentiating factor is transposition. A case can be made for a currently-accepted standard range for the xylophone as well as for the marimba, but ranges have continually changed over time and are really at the discretion of manufacturers and players. My 5.0 octave Deagan 268 xylophone is a case in point, as are some instruments called for in the repertoire, such as the tenor xylophone part in Orff’s Catulli Carmina.

Bob Becker (May 2013). Reprinted by permission

Two-Mallet Performance

Bob’s interview with Gene Koshinski (re two-mallet performance)

By Bob Becker, first published October 7, 2009

My name is Gene Koshinski, Professor of Percussion at University of Minnesota Duluth. I am currently finishing a document as my final step to completing my doctoral degree at The Hartt School in Hartford, CT. The title of my paper is: “From West Africa, through Vaudeville, to the Concert Hall: The Evolution of Two-Mallet Keyboard Percussion Solo Performance.” Would you be willing to take a few minutes of your time to put into words your approach to two-mallet technique and performance? It would be very helpful to have your valuable comments. If you are able to help, below are a few example questions which prompt the type of information I am interested in.

September 28, 2009

GK: Can you describe your two-mallet grip? Where is the fulcrum, what is the job of each finger, what parts of your hand/fingers are in contact with the stick, etc.?

BB: When I hold two mallets for keyboard playing, as opposed to timpani or some other kinds of playing with two sticks, my grip is similar to the “finger grip” described by George Hamilton Green in some of his publications. The thumb and index finger are opposed on the shaft, and the other fingers curl naturally around it. Green, like many other performers, specifies that the little finger does not touch the shaft or handle of the mallet, and so is essentially unused in his grip. I don’t follow that aspect of his method – I generally use the little finger as an equal contributor to controlling the stroke, and so I keep my little finger on the stick most of the time.

GK: Can you describe your general two-mallet stroke?

BB: Although I don’t use Green’s finger grip when playing snare drum (whether I’m using matched or traditional grip), my use of fingers and wrist in making and controlling strokes on the drum and the xylophone is similar. I have always felt an alliance in percussion playing between snare drum and xylophone on one hand, and timpani and marimba on the other. When playing the xylophone, my hand position is generally palms down, with the hands no more than an inch above the keyboard, and the stroke is made almost entirely with the wrist. The stroke height is also kept to only two or three inches, no matter what the dynamic. It’s described in detail in all of George Green’s lesson books. This technique can still produce a good and a big sound, but it requires a lot of forearm strength and endurance, and is not easily mastered. Even so, it is very useful on all of the percussion instruments. Furthermore, as I always point out to students, this is a great way to play the xylophone, but it is not the only way. I believe any serious performer should be in command of many grips, stroke types and wrist motions, and be able to use them freely for creative expression.

GK: What other types of strokes do you use?

BB: All other types of strokes.

GK: What is your approach to rolling (single notes as well as double stops)?

BB: I am often asked about this, both regarding my own playing and the performance practice of early twentieth century xylophonists. From a historical perspective based on the recorded archive, we know many roll speeds and articulations were used between, say, 1905 and 1930, and most all of them are persuasive in their way.

George Hamilton Green’s rolls had a distinctive and uniquely beautiful quality that I have tried to emulate for my basic approach when playing in that style. Green used a comparatively slow speed for tremolos on both single and double notes, and so the sound is always clear, resonant and never choked. Furthermore, Green followed a consistent rule in his playing, always commencing tremolos with the left hand. This sticking is clearly marked throughout the exercises in his lesson books and in many of his published solo pieces. Although he was left-handed, Green’s approach makes sense on a number of levels. His stick position was consistently left in front of right, which was the standard two-mallet set-up taught for decades (all of my teachers also preferred this position). His approach to tremolos on the upper manual was to consistently lead with the left hand, which played in the center of the bar, while the right hand always played on the extreme near end of the bar. This method makes for a very secure and consistent feeling, even though it may seem counter-intuitive at times. I should also mention that tremolos are the only case where Green suggests playing in the center of the upper manual by either hand. His method was always to play the upper manual on the near ends of the bars.

Green always used a left hand lead when playing double notes as well, and in this context the technique makes musical sense. Obviously, when playing rolls with two notes, whether the player is holding two mallets with two hands or with one, there are three possible ways to begin: 1) both notes together; 2) starting on the upper note; and 3) starting on the lower note. In addition, 1) is simply a particular way of playing 2) or 3), since the initial double stop must be followed by either the higher or lower note. Commencing the tremolo with both notes together produces a mild sforzando attack, which can be very useful in certain situations. Each of the three options produces a distinctly different effect, but Green always used the third method. In his musical style, double stop rolls were usually used when playing a melody, with the left hand accompanying the right with a lower, harmonizing note. In this circumstance, a roll started on the upper melody note always communicates a slight sense of intrusion when the lower note suddenly appears a split second later. When the roll is started on the lower harmony note, the later entrance of the melody note is accepted more quickly and naturally by the ear. The result is a rounder, more legato effect.

When discussing trill and tremolo effects on percussion instruments, an important question to consider is: Do rolls truly give an illusion of sustained sound, or are they rather a rhythmic and/or expressive effect? Percussionists usually are taught early on that rolling (on any instrument) is the way to produce a sustained sound, and this notion becomes an ingrained part of our technique and conception, even though the tremolo effect may not be perceived by non-percussionists in this way at all. It can be difficult for percussionists to step back and listen objectively to some basic aspects of their playing – especially techniques that are taught as fundamental to the instruments.

When using tremolos, I try to stay aware of all the expressive possibilities of attack, sticking, speed and voicing that are available. I always want to incorporate a variety of approaches in my playing in order to maintain interest and help create a feeling of spontaneity and life in the sound and phrasing.

GK: What is your approach to sticking?

BB: Sticking is one of the most expressive tools in percussion playing. It also can be a very personal means for interpretation, on drums just as much as on keyboard instruments. Many performers, perhaps most notably the late Fred D. Hinger, have pointed out a natural tendency for double strokes to bring out the “leading sound” – that is, the second stroke in a double receives more weight in order to achieve clear articulation. I use this idea a great deal in all of my playing. On the xylophone, many of the special ragtime sticking effects developed by George Hamilton Green involve linked double strokes in both hands. When the leading sound idea is applied in these patterns a very exciting rhythmic intensity can result.

The options for including both single and double strokes in patterns and phrases quickly become very large as the total number of strokes involved increases. In my opinion, having options is desirable in all areas of musical performance, and so an awareness and understanding of sticking possibilities is extremely valuable. If you’re interested in a detailed analysis of this aspect of sticking patterns, take a look at my recent book Rudimental Arithmetic.

GK: What is your approach to mallet choice?

BB: I own lots of sticks and mallets, many of them custom made for me. Like most professional percussionists, I also own lots of instruments. Mating a specific mallet to a specific instrument for a specific sound in a specific passage to be played in a specific acoustic is a very creative and interesting aspect of percussion performance. Again, I’m interested in having options. In general, I try to keep my mind and ears open to special or unusual sounds and articulations, but finally, I make selections based on what I hear and feel in the music. Of course, if I’m playing in an orchestra, the conductor’s opinion may also carry some weight.

Nathaniel Bartlett’s New Paradigm in Percussion Performance

Brant Blackard – After Syrinx II

Behn Gillece – Why Try To Change Me Now

A solo performance of a beautiful ballad, “Why Try To Change Me Now” (Coleman-McCarthy). Upon discovering this tune, I thought it was the perfect ballad for solo vibes. This piece is performed on the Malletech Love Vibe, which gives amazing options for dynamics and expressiveness.