Michael Burritt – III. Home from Home Trilogy

Michael Burritt – II. White Pines from Home Trilogy

Michael Burritt – I. Painted Hills from Home Trilogy

Andy Harnsberger – Phoenix

Colleen Bernstein – From My Little Island

Andy Harnsberger – Serpent

Two Mexican Dances (by Gordon Stout)

If you enjoyed this music, “Two Mexican Dances” is now available for purchase.

Movement Two

Tony Miceli: Video Page

Good Vibes Milestones

Fantasy and Variations for Annie

Andrea Venet: Hop (3) and Dance of Passion

Dance of Passion from My Little Island by Robert Aldridge

Andy Harnsberger – April Sun

Nathaniel Bartlett: features live marimba + computer performance

Nathaniel Bartlett: features audio from album timeSpacePlace

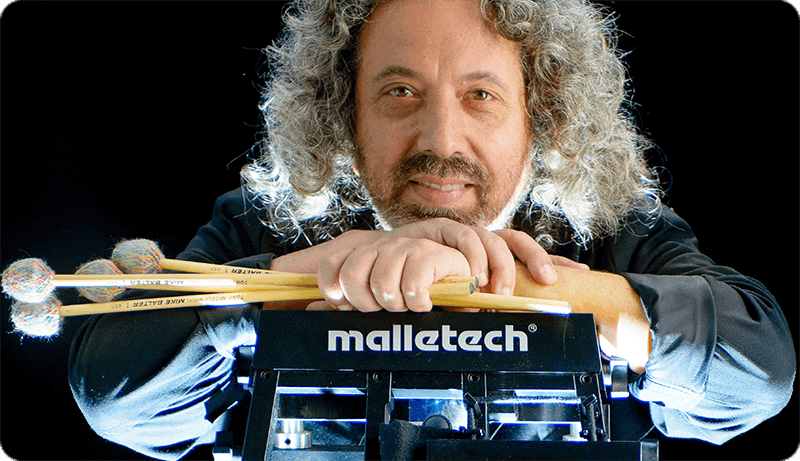

Sergei Golovko

Sergei is International Master Educator Endorser with Malletech company (USA) and plays exclusively on Malletech instruments – the world’s best marimbas and xylophones.

Ed Smith – Neptune – PASIC ’12

Ed Smith performs his original composition “Neptune” on a Malletech Love Vibe at PASIC 2012 in Austin, TX. Ed’s music career as a jazz vibraphonist and percussionist spans more than three decades. In 1992, Ed helped form the internationally recognized world percussion group, D’Drum. A PBS short film about the group and their world travels won an Emmy in 1999. As a member of D’Drum, Ed recently collaborated with Stewart Copeland on a world music concerto called “Gamelan D’Drum.” Ed teaches vibes and Balinese gamelan at the University of North Texas and vibes at SMU.

Rounders for solo marimba and percussion trio by Michael Burritt

Rounders for solo marimba and percussion trio by Michael Burritt. Performed by Michael Burritt and members of the Eastman Percussion Ensemble (Ivan Trevino, Amy Garapic, and Mark Boseman), in June 2011 at the Eastman School of Music.

Joe Locke/Geoffrey Keezer Group at PASIC ’12

The Joe Locke/Geoffrey Keezer Group performing “Her Sanctuary” at PASIC 2012. World Debut of the Malletech Ωmega Vibe. Joe Locke on Vibes; Geoffrey Keezer on Keyboards; Mike Pope on Bass; Marvin “Smitty” Smith on Drums. Director of Photography Bobby Longoria.

Ed Smith – I Loves You Porgy – TMEA ’13

Ed Smith performs “I Loves You Porgy” on a Malletech Ωmega Vibe at TMEA 2013 in San Antonio, TX. Ed’s music career as a jazz vibraphonist and percussionist spans more than three decades. In 1992, Ed helped form the internationally recognized world percussion group, D’Drum. A PBS short film about the group and their world travels won an Emmy in 1999. As a member of D’Drum, Ed recently collaborated with Stewart Copeland on a world music concerto called “Gamelan D’Drum.” Ed teaches vibes and Balinese gamelan at the University of North Texas and vibes at SMU. “I Loves You Porgy” is published by Warner/Chappell and is used here with permission from the publisher

Burritt Variations by Alejandro Viñao

Performed by Michael Burritt, Professor of Percussion at the Eastman School of Music.

Invitation Tony Miceli and Behn Gillece

Bob Becker: Mudra

Performed by Bob Becker and Amadinda Percussion Group in Budapest, 2005.

Eastman Percussion Ensemble: Fandango 13

Swanee – Bob Becker and Yurika Kimura Duo

Xylophone (Malletech XB4.0- Bob Becker soloist model) Bob Becker Marimba (Malletech Imperial Grand – Leigh Howard Stevens’s personal instrument!!!) Yurika Kimura Bob and Yurika played George Gershwin’s Swanee on their showcase concert at PASIC 2013. This music is available from Keyboard Percussion Publications(KPP).

2+1 Marimba Duo

2+1 for Marimba duo, by Ivan Trevino performed by Escape Ten (Escape X), Annie Stevens, Andrea Venet, at Eastman School of Music 2013

Behn Gillece and Tony Miceli – One of Those Things

Behn Gillece – Uma Para Agosto

Behn Gillece’s solo performance of “Uma Para Agosto.” Hear the original version on MINDSET, available May 15! Loosely based in a bossa nova style, “Uma Para Agosto” translates to One For August, the month in which the tune was written. This piece is performed on the Malletech Love Vibe, which gives amazing options for dynamics and expressiveness.

Palta by Bob Becker – NEXUS

From Super Percussion, Tokyo Music Joy Festival on February 25, 1988. Performed by NEXUS with Steve Gadd, Soloist.

Escape Ten – Radiohead

Escape Ten plays ‘Weird Fish Pyramids’ – music by Radiohead, arranged by Andrea Venet

Sara’s Song by Michael Burritt

Sara’s Song was written for one of my best friends daughters wedding, Sara Sartarelli. I dedicate it to the Sartarelli family one and all!

Blue Ridge by Michael Burritt

Blue Ridge by Michael Burritt

Burritt Variations

Burritt Variations for solo marimba, by Alejandro Viñao Performed by Andrea Venet

Dave Hagedorn

When I first started listening to jazz, I quickly gravitated to the ECM catalogue. The chamber ensembles, the emphasis on space and dynamic, the profound improvisation, it all spoke to me. One of my favorite discoveries during this time was Ralph Towner, so I thought it would be perfect to cover his trademark song Icarus. Joining me here is the esteemed Dave Hagedorn, on the Malletech love vibe. This vibraphone has a pedal that controls both the dampers and the vibrato effect, which is created using sliding plates. It sounds amazing, and I am very grateful to Dave for his work here. Enjoy!

My Favorite Things

Escape X Duo – Andrea Venet and Annie Stevens Live performance at Virginia Tech, September 2015. Arrangement by Andrea Venet

Joe Locke “Ain’t No Sunshine”

The Joe Locke Group feat. vocalist Kenny Washington and Ernesto Simpson (drums), Darryl Hall (bass), Danny Grissett (piano)

Weight Vs Hardness

For a manufacturer to controll the hardness of a mallet is easy. For a manufacturer to control the weight of a mallet is easy. For a manufacturer to control both weight and hardness simultaneously in each model of a line is tedious in the research stage, time consuming and frustrating in the development stage and usually more expensive to manufacture. Perhaps that is the reason that no one ever bothered to do it until MALLETECH(tm).

The most common and least expensive way to make a line of mallets of various hardnesses is for the manufacturer to simply ignore weight as a factor. To achieve a wide range of models from the same rubber mold, manufacturers usually control only the durometer (i.e., the hardness) of the ball, never considering the musically and technically important point that the successive models in a line may end up having no sensible weight relationship to one another.

Because this method of “designing” a line of mallets is so common, so are the following two problems:

1.) You like the weight of a particular model, but it is not quite hard enough for a particular piece. So, you buy the next harder model of that brand (if you can figure out from the crazy model numbers and one word description which model is the next harder), and it turns out to be much too heavy — or too light!

2.) You like the hardness of a particluar model but it’s too heavy for the fast passage work in the piece you’re working on. You want a lighter mallet of nearly identical hardness. How do you find it? Do you know someone who owns almost every mallet made — and is willing to loan you them to try? How about calling a music store and asking them to weigh a few models you are considering? (“It’s OK, put me on hold while you get out the postal scale”.) Do you happen to live near a percussion store that keeps a marimba and vibes set up for customers to try out mallets — and stocks a wide selection?

These are only two of the types of weight vs. hardness problems percussionists have had to put up with for years. A more expensive procedure than just controlling durometer is to change elastomers (i.e., type of rubber compound) as the durometer of the model changes, thereby controling the specific gravity (i.e., weight) of the core as well. MALLETECH(tm) has used this method on the Friedman and Samuels lines to keep the two models in each line very similar in weight. After two years of experiments on the Natural Rubber Series, we have achieved almost identical weights on the four different models. To appreciate what a breakthrough this is, you must try them side by side with any other line of unwrapped mallet.

MALLETECH(tm) has also added a third, still more complex method to control weight and hardness. To understand why this is an advance in mallet technology it is necessary to know that thermoplastics can be controlled very closely for specific gravity, and that certain elastomer compounds can be closely controlled for hardness. By combining these two technologies in one design, we can take advantage of the precise weight control of thermoplastics while adjusting hardness through the science of elastomers. This is the system used in the Stevens and Concerto lines. What all this means to the performer is that there is a smooth, predictable and minor change of weight from model to model. Each of the regular models in these two lines gets slightly lighter as they get harder.

As a result of all of this research, MALLETECH(tm) can now offer lines that are designed so that the weight of the model increases along with hardness ; lines in which weight decreases along with hardness; and lines in which weight remains the same as hardness increases. As reflected in our premium prices, this is not the easiest, fastest or cheapest way to design and make mallets, but we feel it is the most sensible and musical from the standpoint of the performer. MALLETECH(tm) believes that when you pick up the next harder or softer model in a line of mallets, it should feel like a member of the same family. If it says MALLETECH(tm) on the handle, it will.

Wrapping & Stitching

Most marimba and vibe mallets on the market today are wrapped and stitched. That’s about all you can say about them. The wrapping is medium tight, the stictching holds it all together and the finished mallet is often very pretty to look at. At MALLETECH(tm), life is not so simple. Most of our mallets have special performance characteristics that require tension adjustments as the mallet is wrapped. Many models have two or more layers of wrapping that need to be wound at different angles. Others have internal stitching that is below the playing surface so that it doesn’t affect your performance.

One thing you will find missing on all MALLETECH(tm) mallets is decorative reinforcement stictching anywhere near the playing area. When the idea of stitching only the very tip and next to the handle of the mallet was introduced on the first Stevens mallets almost twenty years ago, many players couldn’t find the stictching and thought the mallets were held together with glue. This simple advancement, now found on all MALLETECH(tm) models (and, we are proud to confess, a few imitators!), allows the player to use the “fresh”, unworn yarn near the tip, for the very softest of rolls or special effects.

Of course, this stictching feature would be wasted on a mallet that wasn’t wrapped properly. While all of our mallets are hand-stitched, some styles of wrapping can be done better by machine. Such as winding vibe mallets very tightly. We have the most advanced machine in the industry. Unlike other winding machines, it can make tension and angle adjustments in the middle of wrapping a mallet, permitting us to build-in audible performance features other brands just can’t match. But some things are too subtle for even our one-of-a-kind machine, so mallets like the Stevens line are still completely hand-wound and stitched. Check the tension and consistency of wrap on our marimba mallets. Now check another brand. Ours are looser, but also more regular. And because they are looser and more regular, they offer better dynamic control, less contact noise and smoother rolls. Check the tension and regularity of our vibe mallets by pushing hard on the yarn under the ball near the handle. Now check another brand. Ours are tighter and smoother. And because they are tighter and smoother, they project better, wear longer and slap less.

All of these advances in design and technology, as well as the great care we exercise in the crafting of mallets, is for two purposes: so that you can have the very best tools with which to make music, and so that we can keep our reputation as the best mallet maker in the world.

Handles

Taste, tone, ticks, handle types: The research and development of the Orchestra Series

Is mallet choice for orchestral excerpts strictly a matter of taste? Is preference for rattan or birch handles just a matter of different “feel”? Is good and bad tone just a matter of opinion?

Before MALLETECH(tm) entered the already over-supplied market of unwrapped mallets for xylophone and bells, we wanted to take a closer look at what was already available, test new materials, and see if there was really a need for more unwrapped mallets. Some startling discoveries were made in our listening and playing tests which we hope you will find interesting and educational.

It will come as no surprise to most experienced players that sight, feel, and distance from the instrument have a definitive effect on percieved sound. Professional orchestral players in our tests often changed their former opinion of a mallet when they were put in the position of the audience and were not able to see what mallet was being used. An important point: The players performing on stage had many opinions as to which mallets they liked the best for selected excerpts, but those wide-ranging opinions narrowed to a consensus when the same players were put in the audience and had to rely only on their ears. As a result of these “blindfold” listening tests, all the materials and sizes of the mallets in the MALLETECH(tm) Orchestra Series were selected on the basis of sound at a distance, with the player’s subjective impression of the “feel” of the mallet as a secondary consideration.

The first real surprise in our tests was that most commercially available mallets were judged by professional orchestral players as having little application to the orchestral literature. In other words, the great bulk of models might be useful for special effects in percussion ensemble or multiple percussion literature, but would be perceived by conductors and professional percussionists as inappropriate for the major mallet parts of the orchestral and wind ensemble literature. The main complaint about the sound of these mallets (other than “too soft”), was that the “tick” associated with the attack was either too prominent, or too far removed from the actual pitch played.

In addition to the above listening tests that were conducted on commercially available mallets, MALLETECH(tm) tested fifty new configurations of ball maeterial, weight, size and handle type. Only a few of these mallets were consistently judged from the audience as having general application to the major orchestral parts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The configurations that were most frequently chosen by professional orchestral percussionists are now the four balls in the Orchestra Series and the two hardest balls of the Natural Rubber Series.

More startling were the results of our handle tests. It seems clear that under certain narrow conditions, the handle influences the tone of an unwrapped mallet. Any differences between birch and rattan handles were inaudible when using a wrapped mallet. However, there is bad news for both confirmed rattan and birch users in the orchestra and wind ensemble. Most noticeable was the fact that in exposed bell solos, a birch handle added a bit of audible noise to the attack — the longer the handle, the more prominent the noise. This “thunk”, as it was most often described, would probably not be audible in tutti passages, but was consistently identified without looking when the bell tones were exposed. It was also found that a thick, heavy rattan handle added some unpleasant noise to a bell attack.

The last finding of our listening tests was perplexing, and will probably not help anyone decide which handle type to buy, but we pass it along anyway. On xylophone, rattan handles were consistently picked for their superior sound qualities at low volume levels, and birch handles were picked for the same reasons at high volume levels!

We think it is safe to say that after such a thorough process of testing and elimination, the MALLETECH(tm) Orchestra Series and the two hardest mallets in the Natural Rubber Series represent the most likely sounds to reach for when performing orchestral and band xylophone and bells. We hope that you can use the information above, and the repertoire suggestions in the individual model descriptions to make educated, musical choices.

Yarn Spinning

Everyone knows that yarn is made of fibers spun together to stay in the shape of a string, rather than in the shape of a lump. But if you want to make extraordinary garments — or extraordinary mallets — there’s a lot more to it than that.

If you unravel a piece of yarn, you’ll find that it is made up of smaller strands of yarn. Each of these main strands is called a ply. The plies themselves can be formed from smaller plies, or from individual “filaments” of the raw material. The raw material will consist of fibers of short lengths, long lengths, mixed lengths, or “continuous filaments”. Generally speaking, longer fibers mean greater strength and shorter fibers mean softer feel, but there are many other variables.

One of these variables is “twist”. Twist is measured in number of turns per inch. All other things being equal, the greater the twist, the stronger the yarn. Unfortunately, as twist and strength increase, softness and loft usually decrease. There is always a trade-off. The individual plies and the finished yarn can even have different twists. The fibers that make up the strands can be pure, mixed, or blended.

The fibers can also be put through a variety of extra processes like brushing (to make the yarn softer to the touch — referred to as the yarn’s “hand”), lofting (to give the yarn more fluff and size), heat treatment (to give the yarn “memory” of its original shape), taslonizing (to give a normally thin but strong yarn more bulk).

Yarn manufacturers don’t know it, but each yarn also has a particular “pitch”. Depending on the combination of the above factors, the contact sound of a yarn can be high above the note played or right in the same octave.

Generally speaking, if the pitch of the contact noise is high, cutting power is improved; if it is low, contact noise becomes less noticeable to the audience.

With all these factors to consider, how does MALLETECH(tm) design a yarn? We start by asking the question, “What is the most critical performance attribute of this model?” Is it lack of contact noise, maximum cutting power, good dynamic shading, rolling smoothness or durability? The yarn designed for the Friedman and Samuels models has great cutting power and good durability. The Concerto yarn has the greatest durability possible while retaining low contact noise. The yarn spun for Stevens and Soloist mallets is designed strictly for tone, rolling smoothness and lack of slap.

You won’t find MALLETECH(tm) yarns at your local knitting store, because everything we use is custom formulated, spun, processed and dyed especially for us. Many players have said that they could hear the difference between our yarns and those of other brands, but now that you know about plies, loft, hand, filament length and twist, you should be able to count, feel and see the difference as well.

Of course, all of the performance characteristics of a yarn discussed above can be amplified, modified or minimized by the precise type of wrapping and stitching techniques used. The special features of a carefully designed yarn can even be destroyed by inept wrapping or stitching. That, of course, is another subject — the subject of Technical Talk No. 1.

Milestones in the Recent History of the Marimba

| 1901

The marimba is scheduled for its North American debut in Buffalo at the Pan-American Exposition. Cancelled due to the assassination of President McKinley in that city. |

| 1903

John Calhoun Deagan in Chicago begins to make xylophones and orchestra bells with chromatic keyboards and resonators. |

| 1908

The Hurtado Brothers tour North America with their chromatic marimba with wooden box-resonators. |

| 1910

The J. C. Deagan Company begins manufacturing of chromatic marimbas. |

| 1933

Clair Omar Musser conducts 100 marimbas at the Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago. They perform arrangements of Wagner’s Pilgrims’ Chorus, Chopin, Elgar and Dvorak’s New World Symphony. |

| 1935

The 100 member International Marimba Symphony Orchestra performs to startled reviews in Europe and at Carnegie Hall in New York City. |

| 1940’s

Brass resonators on marimbas are replaced by cardboard tubes due to rationing of metals for war effort. Marimba range begins to shrink from five octaves to three and a half octaves in response to desire for portability. |

| 1937

Leopold Stokowski toys with idea of adding bass marimba to the string bass section of the orchestra because of its full bass tone. After borrowing one from Clair Omar Musser, wisely decides against it. |

| 1940’s

Clair Omar Musser breaks away from J. C. Deagan Company over issue of rehiring WWII veterans and founds Musser Marimba Company. Creston Concertino composed. |

| 1950’s

Vida Chenoweth performs first solo marimba recital of all original marimba compositions. Commissions and performs Robert KurkaÕs Concerto for Marimba and Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. |

| 1960’s

Popularity of marimba increases as college music departments develop percussion programs, marimba ensembles and percussion ensembles. Important Japanese composers write works for Keiko Abe. |

| 1970’s and 80’s

Introduction of one-handed rolls, birch handles, single independent strokes and other new techniques by Leigh Howard Stevens spurs a burst of player and composer interest in marimba as solo instrument in USA and Europe. |

| 1980’s and 90’s

Marimba range begins to expand again to size that was common in 1920’s (4 1/2 to 5 octaves). Major composers begin to write for marimba: Druckman, Miki, Reich, Schwantner, Berio, Henze. |

| 1998:

Revival of the marimba orchestra culminates in a performance at West Point, New York on March 28, 1998 with 134 marimbas on stage being simultaneously played upon by 184 marimbists, conducted by Dr. Frederick Fennell. |

Super Smooth Resonator Technology

Why Malletech “SST” (Super Smooth Technology) is such an important advancement in sound

Back in the early days when marimba and xylophone were used mostly in “novelty music,” there was a vaudeville act in which the marimba player stops in the middle of his performance, feigning a problem with the instrument. He taps several times on a particular bar on the sharp keyboard and looks at the audience with a face that says “what’s wrong with this note?” He then moves the bar aside, and with astonishment, pulls a banana out of the resonator! As the band starts back up, he eats the banana, puts the bar back in place and starts playing again, happy, finally, with sound of that note.

Today it would be unusual for a musician to find a banana in a resonator, but it would not be unusual to find, screws, nuts, bolts, rivets, felt pads, tubes within tubes, and numerous structural braces crisscrossing and obstructing the sound field.

What does that do to the resonance?

Malletech has discovered that every single internal encumbrance within the tube creates airflow eddies that disturb and resist smooth airflow. Disturbance and resistance of airflow lowers volume and produces additional, unwanted non-harmonic overtones.

Most marimba manufacturers seem to be proud of the “rich mix of harmonics” that their bottom resonators produce, and some actually use wording similar to that in their advertising. However, bottom-flared, rectangle, teardrop and oval shapes are less sensitive to the fundamental and have hundreds of non-harmonic overtones that distract from a clear sense of pitch. Manufacturers have all known for decades that any shape other than a round resonator tube produces non-harmonic overtones, but all the “school instrument” companies continue to use those shapes because they are far less expensive to manufacture.

Why do those flared and oval resonator shapes (and the internal braces, flap “tuners,” and tubes-within-tubes that those types of designs must have) create “out of focus,” “muddy” bass sounds and uneven volume, bar to bar, note to note? Even with modern “perfect” triple harmonic tuning, marimba bars still contain several disturbing, out of tune overtones and uncontrollable modes of vibration. These out of tune harmonics (frequently “in the cracks” between notes, or at undesirable tri-tones and sevenths) are picked up and amplified by those types of resonators. Why? That’s because flared bottom, oval and rectangular tubes do not contain the natural harmonic series (octaves, fifths, thirds, etc.) that we are used to hearing from strings, woodwind and brass instruments, as well as the best bass organ pipes. They contain literally hundreds of out-of-tune resonances. Blow into a rectangular or oval resonator and you will hear that it is very difficult to hear a fundamental pitch. Blow into a round resonators and it “sings” a clear pitch.

An example of hundreds of overtones is found on a cymbal. When you strike a cymbal, you can’t indentify an exact pitch. There are exact pitches in there, but there are so many of them, so close and randomly structured, that the ear can not pick out an organized pitch structure as it can when the fundamental, octaves, thirds and fifths are predominant — as they are on a bass viol, organ, trombone or piano.

If you don’t know what is meant by “out of focus” and “muddy” tone, listen to a bass bar on an Orff instrument – a rosewood or synthetic bass bar over a rectangular resonator box. While these pre-school and grade-school learning instruments can be “charming,” if you heard the same bar over a round tubular resonator, your mouth would drop open with disbelief that it could be the same bar. Needless to say, over the round tubular resonator, the Orff bar has far more volume and clarity of pitch – it “improves.” This is not an “opinion” or “a matter of personal taste.” This is an acoustic reality that can be heard by any trained musician or music lover once you know the difference. “In tune” is better than “out of tune.” Clear pitch and perfect natural overtones are superior to the alternative.

The same Orff experiment has been done hundreds of times with 5-octave marimbas. Take off the “worst bar” from an instrument that has flared or oval resonators and put it over a Malletech Imperial or Roadster resonator. Mouths drop open and groups of percussionists laugh out loud the first time they hear the difference. Almost every time, the “bad bar” sounds great on the round resonator.

The reason? Round resonators, plugged on one end, don’t even contain out of tune harmonic pitches. Round tubes only resonate the fundamental and desirable natural overtones. The result is that the “bad” sounds of the bar are not amplified and therefore the tone in the low range is cleaner, more “in focus” and therefore, much more powerful.

That is the theory behind our development of SST. While it is a very expensive process to manufacturer, we have eliminated the last bits of internal resistance to natural harmonic resonance. While our silver-soldered (brass) and “tig-welded” (aluminum) resonators are the current world standard for power and in-tune harmonic content, smoothly bent tubes, without the little bumps and corners are a little bit better. How much better? Enough that the musicians who have participated in our “backs-turned blindfold tests” can clearly hear the improvement. Tested with the same bar, the SST resonators are a bit louder, a bit longer ringing and “cleaner” in pitch – especially when combined with higher notes.

Patented. Available since late 2011.

The Acoustics of Resonators

by Leigh Howard Stevens

Acoustics of Keyboard Percussion Instruments

There is an old joke told by orchestral musicians about harpists.

“Harp players spend half of their time tuning their harps and the other half playing out of tune.”

I’ve written this article with the hope that similar jokes about marimbists never develop. That is not such an easy task, because there is a vast amount of misunderstanding and percussive folklore to overcome. Even today, almost ten years after the (re)introduction of tunable resonators to the marketplace, there is still great confusion about what they are for, what actually happens to the bars and resonators in different weather conditions, what tunable resonators can do to compensate for those conditions, and perhaps even more confusingly, what to do if you don’t have tunable resonators…

Click button below to download the entire article (PDF)

Mallet Suggestions

|

By Leigh Howard Stevens |

|

About the Marimba

By Leigh Howard Stevens

The marimba is at once one of the oldest and one of the newest musical instruments. While the first concerto for marimba and orchestra wasn’t composed until 1935 (by American Paul Creston), the marimba dates back thousands of years and may actually be the oldest musical instrument known to man.

A seven note lithophone, or “stone marimba” was discovered in Vietnam in 1949 by French pre-historian Georges Condominas. It is estimated to be 5,000 years old, which makes it the oldest known musical instrument specimen in the world. The bars of this marimba-like instrument, which range from 40 to 26 inches in length, were perfectly tuned to a Javanese pentatonic scale by the deliberate chipping and flaking of some ancient instrument maker. Similar instruments have also been found in the burial chambers of Egypt, and in other parts of Africa.

The wooden variety of this family of instruments appears to be indigenous to many primitive cultures in Asia and Africa. The marimba is differentiated from the xylophone-like instruments by the addition of a separate acoustic amplifier for each note. The idea of adding an identically tuned hollowed out gourd or other vessel to amplify and enrich each tone bar of the instrument was a stroke of genius of some unidentified primitive mind.

It appears that the marimba came to Central and South America with slave trade, bypassing Europe until North Americans brought the instrument to the Continent sometime in the second decade of this century. For this reason, the great European master composers were unaware of the marimba. The xylophone had a separate development in Europe, being played by roving Gypsy musicians and eventually making its orchestral music debut in 1874 in Saint-Sa‘ns’ Danse Macabre.

The evolution of the marimba from a lap-held, crudely tuned instrument of a few notes to today’s “Grand Soloist Marimba” came about strictly in the Americas. The change from one diatonic to two chromatic rows of tone-bars, arranged like a piano, was the contribution of Sebastian Hurtado, a Guatemalan, in about 1880. The perfection of the tuning of the bars, the addition of metal tubular resonators for greater volume, and the concept of tunable resonators for weather compensation was all accomplished in North America.

The vibraphone (or “vibes”), the jazzy little cousin of the marimba, is also an American invention (1916), and is distinguished by aluminum-alloy bars and a pedal system designed to dampen the long-ringing bars. The vibraphone is often fitted with an electric fan-like mechanism in the tops of the resonator tubes, which, when activated, gives the instrument a steady vibrato. Other instruments in the keyboard percussion family are the xylophone (essentially a small, high-pitched, brilliantly brittle-toned marimba, with or without resonators); the glockenspiel or orchestra bells (small steel bars and narrow, very high-pitched range); and chimes or tubular bells (long tubes of special brass alloy, tuned to imitate church bells or carillon).

Dr Splatbar

1. Keep your wrists stiff and use your forearms to hit the bars. Don’t worry about what your teacher says, this is the most basic stroke used by beginners. Only great players keep their arms level and stroke with their wrist. In fact, artists like Gordon Stout and Bob Becker take it to such a silly extreme that it looks like their forearms move up a little when the mallet goes down. Why would you want to look like one of those guys when you were playing — people might say you were just a copy cat.

2. Use big tall strokes. Hitting correct notes is too easy if you keep the mallet heads one or two inches away from the keyboard. If you do this for a couple of years, playing keyboard percussion instruments might become so boring you might even give it up and have wasted all that practice time. Challenge yourself: never play from lower than six inches away from the bars. Use big, manly strokes. Plus, stroking the instrument from high up looks more difficult and will impress audience members who know nothing about keyboard percussion instruments (it might even impress audience members who know very little about keyboard percussion instruments…).

3. Avoid Piston Strokes whenever possible. Don’t be fooled by euphemisms: Some people call them “Down Up” strokes, or “Full Strokes”. Avoid these two-part strokes that start and stop at the same height and just go down to the bar and back up. Can you imagine practicing using the same simple stroke over and over? How boring! That would make music like learning tennis.

3a. Use complicated three part motions of the mallet head every time you play a note. These strokes are easy to recognize by the fact that they start with an upward preparation before the actual stroke. They could be described, “Up Down Up”. These strokes burn off extra calories and assure that you will never be a fat marimba player. They are less accurate which serves to keep you on your toes. Also, because of their three parts, they can’t be performed at a rapid rate. This can actually serve as a handy reminder: if you notice you’re using a stroke with preparation, you know you’re probably practicing. You can always switch to a piston stroke later on if you decide to work a passage up to speed.

4. Don’t waste your valuable time learning scales and arpeggios. If you have managed to get this far without them, why bother? Sure, there are people with half your intelligence who learned them all in a couple of weeks, but what kind of social life did they have in the meantime? The most important thing is to play and enjoy music. Life is too short for exercises. Dr. Splatbar says, “Groove, don’t grind!”

5. Don’t repeat. Don’t repeat. See? It only drives any mistakes you might be making into your brain . George Lawrence Stone and George Green, two of the greatest xylophone players of all time, both recommended repeating short passages over and over. Look what good it did for them — they have both been dead since before you even knew what a mallet was! While we can’t be sure that repeating short passages and death were connected, it’s better to be safe. Dr. Splatbar advises, “Start at the beginning. Go to the end. Do something else.” Avoiding repetitive practice of small sections keeps the piece fresh.

6. When reading, keep the music stand high, so you can’t see the bars out of your peripheral vision. First of all, looking would be cheating. Second of all, since keyboard percussion instruments are the only melodic instruments that you don’t touch with your hands (aside from timpani and the Theremin), there is something tidy about not looking at them either. Plus, it’s very impressive to tell people that you neither touch nor look at your instrument, and still manage to sight read music on it. . . after a fashion.

7. Ask your teacher frequently whether you should be striking the sharps on the ends or near the centers. Don’t waste time examining how the sound changes as you move your striking spot on the bar — even if you did manage to figure this out and started making these decisions on your own, your teacher might feel rejected. Gordon Stout teaches that for the first year or so you should only strike the very ends of the sharps and off center of the naturals. He says having only one permissible striking spot per note helps develop a better feel for intervallic distances around the keyboard. Dr. Splatbar disagrees: “Striking on the string or halfway between the end and the string adds an impulsive, improvisational, and unfettered emotional dimension to your playing.”

8. Don’t plan your practice time. Practice time for many of us is limited, so enjoy it. If you took the first five minutes of every practice session and planned your time and decided what single thing you most wanted to accomplish, think how rotten you would feel if you used up your time without reaching that goal. By planning your practice you are actually setting yourself up for disappointment. If there is nothing special you need to accomplish today, there won’t be any frustration about not doing it!

9. Don’t use your fingers. Save them for things in life that require fine control: writing, turning stereo dials, brushing your teeth, playing the piano — not crude things like bashing percussion instruments.

10. Make sure the keyboard is at an uncomfortable height. Having the instrument at the perfect height for your anatomy fosters complacency. Discomfort fights boredom. Do the following test: Play some “air marimba” or vibes and notice what height you naturally want to strike. If your keyboard is about the same height, adjust it with magazines, blocks or a built-in height adjustment mechanism until it feels odd. Here are some of the beneficial signs of awkwardness: the mallet handles are at a 45¡ angle to the bars when the head contacts the instrument; the handles occasionally click against the bars; your legs are tense from flexing at the knees; your back aches. Lastly, watch for that sensation of feeling like you might be more comfortable sitting down. Not only is this a sign that the keyboard is properly adjusted too high for you, it’s also a classic symptom of needing a break. Go ahead!

*Dr. Splatbar plays concerts, records albums, designs marimbas and mallets and has authored a book on four mallet playing, Method of Movement, all under the pseudonym Leigh Howard Stevens.

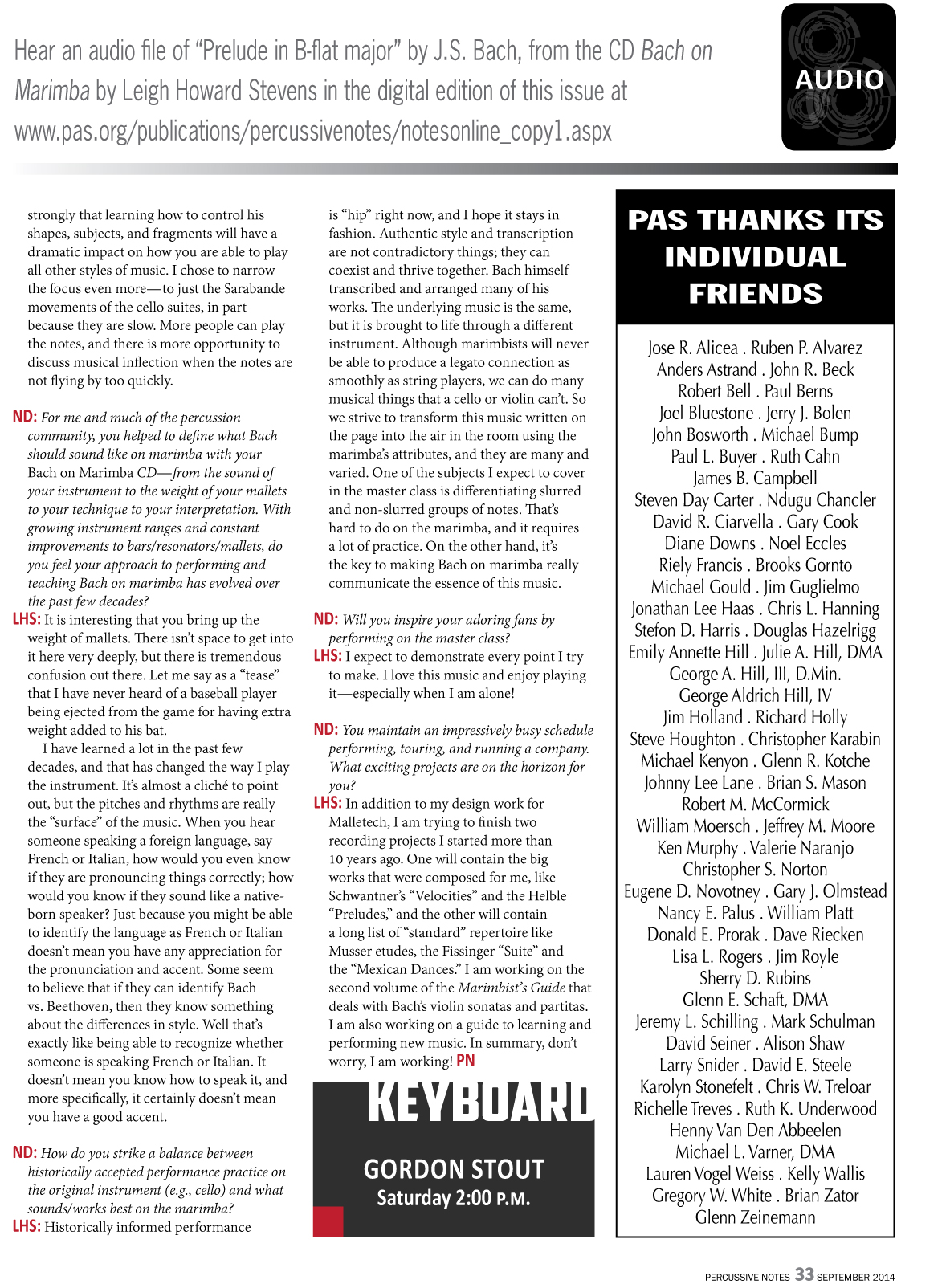

Catching Up with Leigh Howard Stevens

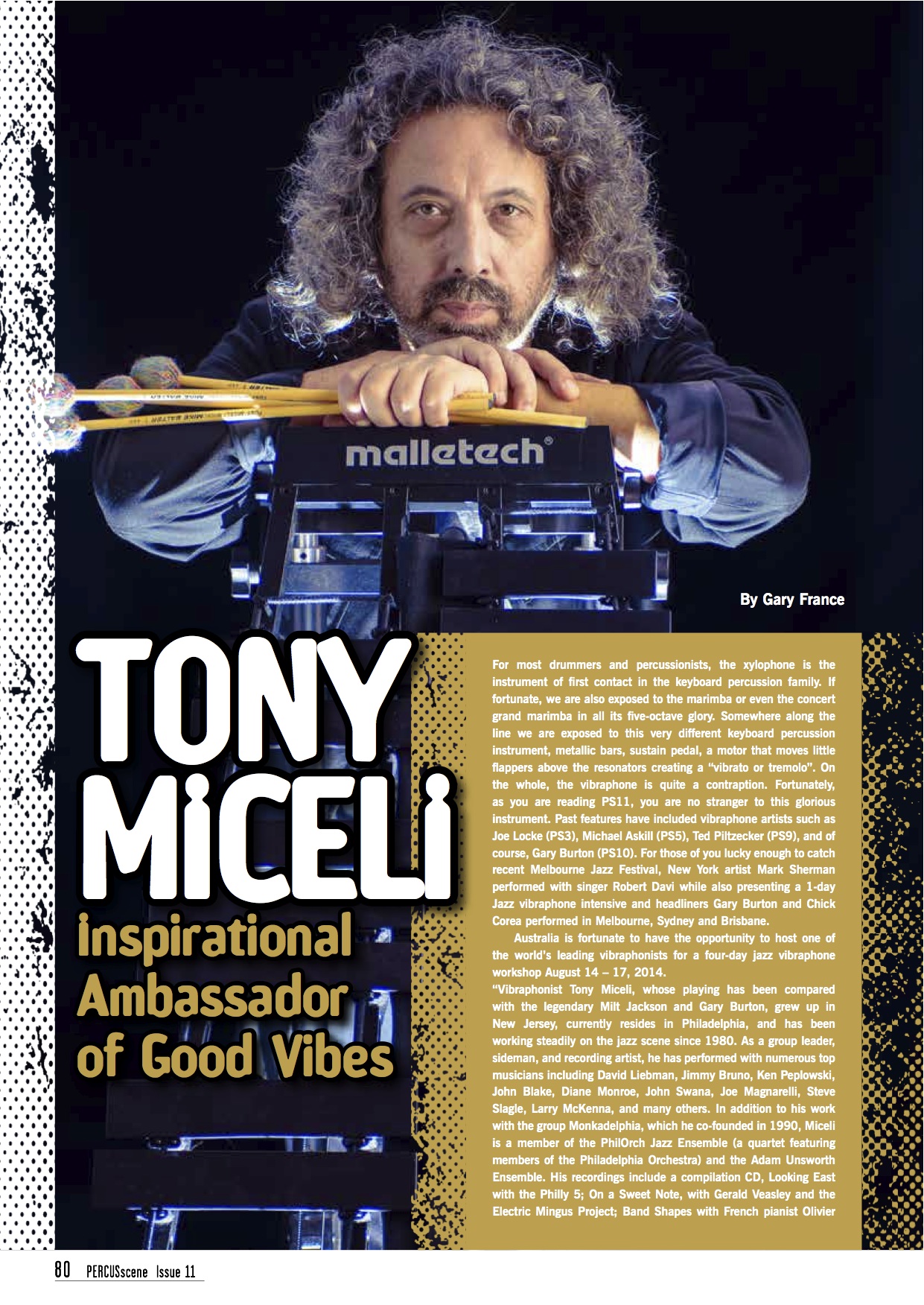

Tony Miceli: Inspirational Ambassador of Good Vibes

Ωmega Vibe Roundtable

Leigh H Stevens, Joe Locke, Mike Pope and Ton Risco spent a day in the Malletech putting the final prototype of the new Ωmega Vibe through its paces. When the day was over, they were exhausted but extremely pleased. Here they discuss the process of developing this game changing instrument and review the features that make this instrument so special.

The Omega Dampening System

The dampening on the Malletech Omega system is really incredible and different from all the other vibraphones. AND it’s very very quiet.

Ωmega Vibe Resonator Tuning – with Joe Locke & LHS

Joe Locke and Leigh H. Stevens show how the resonator tuning system on the new Malletech Ωmega Vibe is one of the many game-changing features that make this Vibe the state of the art. Every feature of the Ωmega Vibe was developed with the input of pros who spend their lives playing, carrying, setting up and breaking down vibes. We used this input to develop what we believe is the most impressive and versatile vibraphone ever made.

Ωmega Vibe – Vibrato System Demonstration

Joe Locke and Leigh H. Stevens demonstrate the game-changing vibrato system on the Malletech Ωmega Vibe. Every feature of the Ωmega Vibe was developed with the input of pros who spend their lives playing, carrying, setting up and breaking down vibes. We used this input to develop what we believe is the most impressive and versatile vibraphone ever made.

Ωmega Vibe – Progressive Dampening System

Leigh H. Stevens reviews the progressive dampening features on the Malletech Ωmega Vibe. Every feature of the Ωmega Vibe was developed with the input of pros who spend their lives playing, carrying, setting up and breaking down vibes. We used this input to develop what we believe is the most impressive and versatile vibraphone ever made.

Ωmega Vibe – Pull Rod

Joe Locke demonstrates how Malletech has completely re-thought the Pull Rod on the Ωmega Vibe. Every feature of the Ωmega Vibe was developed with the input of pros who spend their lives playing, carrying, setting up and breaking down vibes. We used this input to develop what we believe is the most impressive and versatile vibraphone ever made.

Ωmega Vibe – Frame Set Up

Joe Locke sets up the Malletech Ωmega Vibe frame…in under 2 minutes! Every feature of the Ωmega Vibe was developed with the input of pros who spend their lives playing, carrying, setting up and breaking down vibes. We used this input to develop what we believe is the most impressive and versatile vibraphone ever made.

Ωmega Vibe – Resonator Assembly

Leigh H. Stevens shows how easy it is to drop in the resonator tubes on the Malletech Ωmega Vibe. Every feature of the Ωmega Vibe was developed with the input of pros who spend their lives playing, carrying, setting up and breaking down vibes. We used this input to develop what we believe is the most impressive and versatile vibraphone ever made.

Ωmega Vibe – Height Adjustment

Leigh H. Stevens shows how easy it is to adjust the height on the Malletech Ωmega Vibe. Every feature of the Ωmega Vibe was developed with the input of pros who spend their lives playing, carrying, setting up and breaking down vibes. We used this input to develop what we believe is the most impressive and versatile vibraphone ever made.

Ωmega Vibe – Unboxing & Full Set Up Instructions – All 16 Sections

The set up, care and feeding instructions for the Malletech Ωmega Vibe. Everything you need to know from opening the box to playing the first notes. Find out what’s in each box; how to set up the harp; pedal and pull-strap assembly & adjustment; clutch adjustment; the Vibrato system; dropping in the resonators; how to use the tuning stick; putting on the wings and attaching power; installing the bars; dampening adjustments; string tension and contact information.

Michael Burritt talks about his signature mallets

Michael Burritt discusses designing his signature Malletech mallets. Recorded at the 34th Leigh H. Stevens Summer Seminar in 2013.

Michael Burritt is a performer, composer and educator. He is also Professor of Percussion and head of the department at the Eastman School of Music.

Michael Burritt on the Malletech MJB Marimba

Michael Burritt discusses the Malletech MJB Signature Marimba – an instrument he first approached Malletech about creating for him in 2010. He wanted tunable resonators, but with more highs on the highs and more lows on the lows. He wanted a new deco/space-age/wind-swept/tough-guy Harley look, but with traditional furniture quality wooden ends that would look great on a concert stage or in his living room. Recorded at the 34th Leigh H. Stevens Summer Seminar in 2013. Michael Burritt is a performer, composer and educator. He is also Professor of Percussion and head of the department at the Eastman School of Music